This is a story I wrote back in 2010 about Linus Weedwhacker’s oldest son, Carson, when he is an old man. It also introduces the genius Merriweather Maydock who becomes the idol of wizard Evelyn Kelly in the Madame books. Christmas exists in Peracelos at this point and that’s another long story that isn’t nearly as interesting. One of these days I’ll write another Christmas story that I can love as much as this one, but this isn’t that day. This was an experiment that exceeded all expectations and seems to capture the most what I love about Christmas. Please enjoy this repost of Meri’s Christmas. Happy Holidays and God Bless. ~M.M.

Carson poked at the stubborn fire in the cookstove before reluctantly adding more coal. The cramped room refused to warm up this morning. His breath hung in thick white clouds as he kept his back next to the stovepipe. A sharp stab of pain suddenly hit him just above the eyebrows and he muttered an oath. Outside, the brutal wind shook the boards and rattled the window panes. It stirred up the powdery snow, almost looking like a second snowfall. Carson watched it moodily through the blank patch in the frost covered windows. It was dark out, far too dark for eight in the morning; another snow would arrive soon.

Carson caught sight of his reflection in the glass and shuddered. Most complexions couldn’t stand the test of a cold morning and a minor hangover and he was no exception. His white hair hung limply in front of his face as the lines around his mouth and forehead cut deeper. Despite these factors Carson wasn’t a bad-looking fellow; he still had piercing blue eyes, and if his face was a little gaunt and horsey looking, his strong chin and fine nose made up for it.

Carson debated, noting the white frost covering the nail-heads in the wall, whether he should warm up the room with a spell, for Carson was a wizard. He was one of the last wizards in Tereand; there were only a few hundred scattered across the globe now. He hadn’t felt like casting magic much these days, however. One needed a certain fire in the belly to move and shape the elements, a fire that had died when Molly had died in October.

Though Carson looked like a man in his late forties, he was in fact almost seventy years old. The magic had preserved him, unwillingly. He’d never had to suffer arthritis, sciatica, or senility associated with most septuagenarians. His wife hadn’t been so lucky. Molly had been fading those last few years, still as cheerful and patient as she always was. They’d only had thirty-one years together; love had found him a second time, when he hadn’t been looking for it. Carson’s eye wandered to the faded photograph of their wedding day. Molly was fresh and rosy and round, unmarred by the march of time. Carson looked the same, though his hair had been darker and he’d been a good deal happier.

The calendar hung next to it, its last thin page flapping in the draught from the window. For the first time in ages, Carson wondered what day it was.

“Let’s see. The butcher came three days ago… no two days ago. That was Tuesday, so that makes it…”

With a sinking feeling, Carson realized it was Christmas Eve. He hadn’t been looking for it, so it was an unpleasant surprise. He sat in the rocking chair he’d placed by the stove and let his thoughts wander. This time last year, the little wooden house in Ewis Forest had looked quite different. Molly loved Christmas and always made an event out of it. Even through her worsening dementia, she seemed to grow better at Christmas. The treasured memories, the clunky ornaments their children had made ages ago, the smell of fir balsam and cinnamon and wood smoke, everything was clearer to her then and it had given Carson hope.

That hope had been dashed. Now the room stood bare and chilly. There was no tree, no stockings, no paper stars or fir garlands. Carson sighed and held his head in his hands. He didn’t know what to do today. Part of him wanted to go get a tree from the fir copse out back, for old time’s sake. The other part wanted to just stare at the wall all day until it was time to go to bed.

His musings were interrupted by the crunch of hooves on packed snow and the jingle of sleigh bells. Carson was mildly interested. Not many people came down this road, preferring to take the main road instead.

“Must be on their way to Derrit’s Farm. I heard he’s throwing a party tonight,” he muttered to himself (a habit he’d gotten into in the last few months.) “He invited me, of course, but I don’t feel like going. God, I didn’t even think of the date— he asked me weeks ago.”

It was when he heard the sleigh slow to a stop and the driver call “Whoa!” that he actually got out of his chair and looked out his front window. Sure enough, the sleigh had stopped in front of his house.

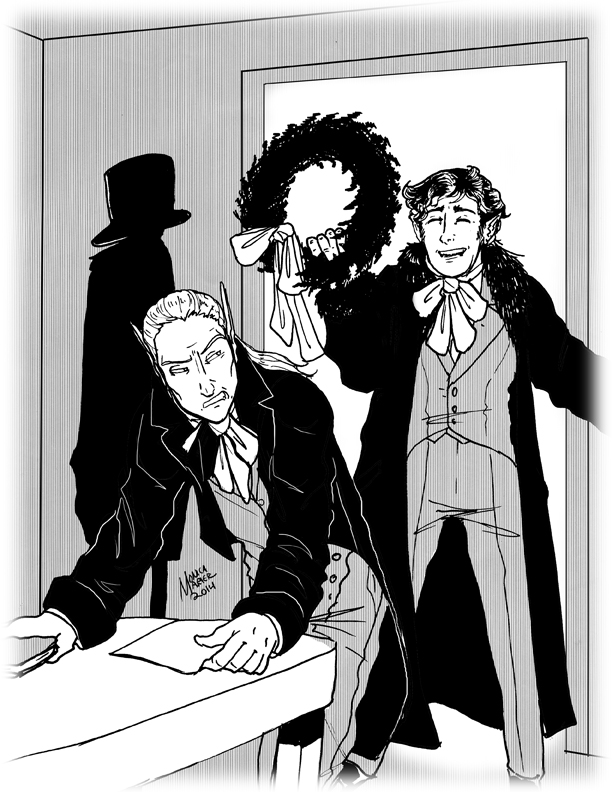

“What in the world?” Carson asked the curtains. The driver, a man in his prime, alighted from the dash. He was dressed in a black coat and a stovepipe hat tied to his head with his scarf to keep the wind from knocking it off. The man surveyed the little house critically and adjusted his elaborate mustache before turning to the sleigh again. Carson could only see a mountain of blankets and fur on the back seat, but judging by the man’s behavior, there were passengers hidden under there. Sure enough, a slight figure emerged, shivering in the harsh wind. The man helped her out of the sleigh, and then assisted the others. There were three of them, all children, by the looks of it, a girl and two boys. Their coats were thin and several inches too short for them; bands of tender skin glowed pink where the cold stung them. The man made no comforting gesture, other than shooing them towards the house and helping up the smallest child when he slipped on a patch of ice and tumbled head first into a snowdrift.

Carson had no idea what they were doing there. He wasn’t expecting any company and the man was an utter stranger. The children were bundled up, so he couldn’t see their faces properly, but he was sure that he’d never seen them either. All the children he’d known had grown up decades ago.

The brusque knock at his door startled him, though he’d been expecting it. He opened the door timidly (for he was shy of strangers) and shivered at the cold blast of air that greeted him.

“Mr. Carson Sfegareth?” asked the man, loudly, to combat the wind that snatched his voice away.

“Yes, that’s me.”

The man faltered a moment, his eyebrows screwed up in confusion. “Mr. Sfegareth Senior?”

“Yes. That’s me,” said Carson again, in slight annoyance.

“I’m sorry to inconvenience you, but I’m afraid you’ll have to take them today. Events have occurred that necessitate my departure.”

“I’m sorry?” asked Carson genuinely lost.

“I said you’ll have to take them today!” shouted the man, thinking Carson hadn’t heard him.

“Take who today?” asked Carson.

The mustachioed man looked nonplussed and there was a long freezing pause on the doorstep as both men sized each other up. The children said nothing, but Carson observed their white faces, wincing with fatigue and pain in the cruel weather.

“I think you better come inside!” said Carson finally.

The four were ushered into the small downstairs room. There were barely enough seats to go around. Carson sat in his rocking chair, while the man sat awkwardly in the hard wooden dining chair. The three children were huddled on the small couch, and looked disappointedly at the empty fireplace.

“Now, please explain to me what this is about,” said Carson in a snappish voice.

“I’m Mr. Fewer,” said the stranger and then said nothing, as if this all the explanation he could give.

“Well, Mr. Fewer,” said Carson eventually, trying to remain polite, “what are you doing here, and who are these children?”

“You didn’t get my letter?” asked Fewer, visibly upset by this.

“It would seem not. The mail out here is rather inconsistent,” said Carson his eyes flitting guiltily to a largish stack of mail that he hadn’t felt like opening.

“I’m the solicitor of the estate of Mr. Oliver Maydock.”

“Oliver…?” asked Carson slowly thinking for the first time in years of his son-in-law.

“The late Oliver Maydock,” Fewer corrected himself. “It happens that he passed away four days ago.”

“How?” asked Carson, his eyes now drifting to the three children.

“Consumption. And since his wife predeceased him you are the last known relative of your grandchildren.”

“Grand…” Carson stopped suddenly, looking at the three pinched faces on the sofa. They mostly looked like their father, all three having inherited Oliver’s brown hair and brown eyes. There were a few features however, the mouths and ears in particular that reminded Carson of their mother, Sarah. Poor Sarah had never had much time on earth. She’d lived just long enough to see her youngest child enter the world before exiting it herself. Carson shooed the thoughts away, to prevent himself from going to pieces, before forcing himself into the present. He was just in time to see Fewer at the door, preparing to leave.

“Now, hold on there, are you suggesting I take these three children now?”

“I’m afraid that’s so. I’m sorry you didn’t get the message, but that’s the way things stand.”

“But I don’t have anything. There’s barely any food — I only have one bed!”

“I’m sure you’ll manage it.”

“But what about their futures, their education? Who’s going to look after that?”

“I’m sure you and your wife can manage that.”

“My wife passed away three months ago.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, sir, but I’m afraid there’s nothing else I can offer you. The bank was kind enough to cancel Mr. Maydock’s debts, but he had no assets no money—nothing.”

“Hang the assets,” shouted Carson, chasing Fewer out into the snow. “I can’t look after three children by myself!”

“Hire a girl, if you can. They’re your responsibility now, so I suggest you get used to the idea. Merry Christmas,” Fewer added as an afterthought.

Carson wanted to jump on the man’s back and shove his “Merry Christmas” back down his throat, but decided instead to get back in the warm as soon as possible. The moment he stepped in the door he was greeted with a blood-chilling yowl. The older boy, who was probably the middle child, was hopping up and down and clutching his tongue. His dark curls bounced up and down as his chubby jowls fluttered. His siblings were watching him impassively.

“What happened in here?” asked Carson shaking the snow from his carpet slippers.

“Patrick touched his tongue to the cookstove,” said the girl solemnly.

“What on Paracelos did he do that for?” asked Carson agog.

“I waneth to thee if ith wath hot,” said Patrick, holding his tongue, but otherwise quite alright.

“So you tested it with your tongue?” asked Carson, feeling mildly concussed by the boy’s logic.

“Well I didn’t want to burn my hanth,” lisped the boy.

“Are you really our grandfather?” asked the girl. There was a tilt to her head and a sobriety in her manner that suggested a girl of the “prunes and prisms” variety. Carson stifled a laugh. Her mother, Sarah, sweet as she was, had had an identical manner that was indicative of a natural born wet hen. The girl’s hair was tied back in a messy plait, and her thin face and tawny eyes glared at him suspiciously.

“Yes, I am…” he paused trying to remember the girl’s name. Carson had only seen her once as a baby. The rest he knew from infrequent correspondence from Sarah in the Colonies. He thought her name started with an H.

“Priscilla,” said the girl. Damn. “You don’t look like a grandfather,” she added.

“What did you think a grandfather would look like?” asked Carson mildly.

Priscilla thought hard about this before answering, “You don’t have a white beard. Or a pipe. Or a round belly.”

“Silly goose, that’s not a grandfather, that’s Father Christmas!” piped up the youngest. He looked like a china doll with glossy brown hair that hung straight down like silk fringe. His eyes were large with irises so dark they were almost black. His cheeks, still red from the cold, were rosy pink dots on his white face and he grinned at his grandfather, showing off perfect little teeth.

“And you are?” asked Carson gently.

“I’m Meriwether. I’m Four and a half! Prissy’s seven and Patrick’s six.”

“So Meriwether…Priscilla…”

“Andth me!” cried Patrick happily, still holding his tongue in his chubby fingers.

“I certainly couldn’t forget you, Patrick,” said Carson with a weary smile.

“Where’s your Christmas tree?” asked Meriwether.

“I haven’t got one… yet,” Carson added quickly, seeing the little mite’s face fall.

“But how is Father Christmas going to come without a tree?” asked Meriwether, his eyes becoming dangerously moist.

“He looks for stockings, Meri, not trees,” said Priscilla primly.

“I don’t see stockings either,” whimpered Meri, his nose beginning to run. “Father Christmas isn’t going to come tonight, is he? He doesn’t even know we live here!” Meri dissolved into noisy tears as he flung himself down on the couch. Patrick, nearby, was looking despondent himself and manfully trying to hold back his tears. He was having less luck with his nose. It’s always the nose, thought Carson with a wince. Prissy was trying to comfort her brothers while keeping a stiff upper lip. She did seem a sweet thing as she dabbed at her leaky brothers with her handkerchief.

“Have you lot eaten yet?” asked Carson.

“No, sir,” said Prissy meekly.

“Call me Granddad, it’s alright,” said Carson. It’s what his other grandchildren called him, although they were all in their thirties now. He shuddered at the thought.

“No, Granddad, we haven’t eaten,” answered Prissy.

“Tell you what then. I’ll make something for you all to eat, while you three get us a tree. Alright?”

“How do we do that?”

“Well, here, take the hatchet and whack a good one down. Not too tall, about three or four feet should do it,” said Carson, handing an axe to Patrick that was nearly as tall as he was. The boy looked at him, an incredulous frown on his chubby face.

“I’m six years old. I’m gonna lose an arm if I try this,” he said.

Carson considered what he’d just attempted to do to get a few minutes alone to think, and felt ill. Snatching the hatchet back he asked, “How about you gather some fir branches, then?”

“Alright, Granddad,” said Prissy obediently ushering Patrick out the door before the boy had a chance to reconsider taking the hatchet.

“Stay within sight of the house. Don’t’ let him eat any red berries,” said Carson, pointing at Patrick. “Or berries of any color for that matter. Wait.” Said Carson suddenly. He just remembered how patched at worn their coats looked.

“Are these your only coats?” he asked.

“Yes, s-Granddad,” said Prissy.

“Alright. Prissy take off your coat and give it to Patrick. Patrick, give your coat to Meri.”

“How did he know we have to do this?” Patrick whispered to his sister.

“I had seven brothers and sisters growing up. I did this a lot,” Carson chuckled.

“Wow. Fourteen kids?” asked Priscilla, who had misunderstood him.

“No, just the seven total,” chuckled Carson as he rolled up the sleeves of his coat, which was now on Prissy. He then grabbed one of Molly’s old kerchiefs and tied it snugly around her head. He bundled the brothers up similarly in his old caps and scarves. When he was satisfied that he wasn’t doing the children an untoward cruelty by sending them outside for another quarter hour, he let them outside, pointing them towards the nearby fir copse. Meri hung back at first and his tiny figure, hidden beneath his bulky wraps (for his brother’s coat was much too large for him) approached Carson.

“Granddad?” he asked. “Do you think Father Christmas will be able to find us?”

“I…” Carson didn’t know what to say. He had nothing even close to a present for any of the children. Still looking down into those dark black eyes, he couldn’t’ bring himself to crush the little heart beneath his old scarf and four inches of gabardine.

“Father Christmas is a clever fellow,” he said finally. “I suspect he’ll manage something…even if it’s only something very small,” he added as the figure bounded into the trees cheerfully after his siblings.

After a meager dinner of potatoes with bread and jam, the rest of the afternoon was spent getting the house ready for a visit from Father Christmas. A modest tree was found and decorated with paper chains, holly, and colorful yarn tippets from Molly’s old knitting basket. An old biscuit tin was cut into a shiny silver star to crown the whole. Creeping spruce and holly clumps were nailed and draped over anything that stood still. Three of Carson’s clean socks were hung over the fireplace, now crackling with a cheerful blaze that seemed to warm the whole house. More warming was the tenderness that Carson felt as he saw the frightened guarded faces of his grandchildren ease into comfortable grins and laughter. Their father’s death was still a close memory, and not a pleasant one, but it seemed they’d been prepared for Oliver’s death for some time. Occasionally the room would lapse into silence as the children grew somber. Then one of them, usually Prissy, would start a new subject to take their minds off their sorrow, and genuine smiles would peek through the forced cheeriness.

They were well-behaved children (for the most part). Carson was impressed. Prissy, it seemed had had the run of the household, despite her tender years and when she offered to help make supper, he was astonished by her proficiency and resourcefulness. Under her management a fine supper was made consisting of quick bread, potatoes, pickled beef with dried blackberry sauce and baked spiced apples. Patrick, with his insatiable curiosity had even managed to discover a lost jar of strawberry preserves in the pantry that Carson had been missing since August. The preserves made a fine desert served with Prissy’s bread. As they retired to bed early, worn out after a harrowing day, Carson thought that maybe the children staying here might not be so terrible arrangement after all… after he partitioned off half of the bedroom and got a spare bed. It might behoove him to write to his sisters and children and ask for help and possibly some clothes.

He was washing the supper dishes when he saw a ghost-like figure draped in trailing white flannel on the staircase. It was Meri, dressed in one of Carson’s nightshirts (the boy’s own nightshirt was full of holes, and unsuitable for the cold upstairs room).

“Meri, are you frightened?” he asked gently, drying his hands as he walked towards the boy. Meri’s face screwed up in agony.

“Are you sure Father Christmas will be able to find us?” he asked mournfully.

“I…think so,” said Carson with a catch in his voice. “I’m certain he will,” he amended quickly. “Don’t you lose sleep over it. In fact I’ll stay up tonight, in case he has any trouble, alright?”

Meri looked suddenly hopeful and, afraid to speak (lest he burst out crying again) he ran up the freezing stairs to the bed that was currently being warmed by his older siblings.

When he was gone, Carson indulged himself in a hopeless sigh, running his hand through his white hair and sighing.

“What in the hell am I going to get them?” he muttered to himself.

“What do little girls and boys like?” he mused. He then remembered that some of Molly’s old knickknacks and such were in a crate in the under-stairs cupboard. After struggling with the crates and choking at the smell of mothballs, he uncovered the very thing. It was a doll Molly had made for their youngest daughter, Emily. It was only just before Emily had announced that she was too old for dolls and was far more interested in painting. The doll had remained unused, and subsequently forgotten, but now, it seemed the beautiful ragdoll with brown yarn hair and an embroidered face would have a mother at last. After airing the doll outside the window for a few hours to diffuse the cloying smell of cedar chips, Carson managed to cram it into the first stocking. He hoped a seven year old wasn’t too old for dolls.

Patrick’s present was a little easier. Carson had only just gotten a new penknife. It had only been used twice and the mother of pearl handle shone brightly without a single scratch. It went into the second stocking. With a sigh, he resigned himself to finding idle carvings on the furniture for the next few weeks. He knew boys like Patrick took rather a long time to remember rules.

Carson paced the floor in agonies over Meri’s present. He ransacked the two crates again, but only found quilting squares, shawls and mantle figurines, nothing a four-year-old could love. He furtively found other things to put in the stockings, a few pennies, walnuts, new pencils, but nothing came to mind as far as Meri went. He had no time to make anything or buy anything. It was hopeless.

“Meri might not lose sleep tonight but I certainly will. Father Christmas,” he spat.

Around one ‘o’ clock, an idea suddenly occurred to him. It was a long shot, and he bit his lip in anxiety over it. A child would get over a ruined Christmas, he knew this from experience, but how would Meri take it, and could Carson deal with it?

The next morning, three tousle-haired sleepy eyed children tiptoed shivering to the couch where their “new granddad” slept. The fire was dead and the room was frozen, but the children’s eyes grew wide at the three fat bulges in the grey wool socks.

“He came! Father Christmas came!” they cried.

Carson awoke at their squealing, and sat up. Prissy’s stuffiness had vanished as she cooed over her new doll; it was her very first, as luck would have it. She named it Sybil on the spot and refused to let her brothers near it. Patrick was overjoyed with his knife and was already trying it out on the wooden mantle before Carson gently asked him not to use it on the furniture. With a growing knot of anxiety, Carson glanced at his youngest grandson who was staring quietly at his present.

In his lap were two smallish leather-bound books. They were old books with yellow pages and damaged spines. Meri flipped through the pages and blinked at the symbols and pictograms inside.

“I got old books,” he said in a husky voice. There were no tears, no tantrums. His heart had been too crushed for that. His own heart aching, Carson sat next to the small boy, ruffled his silky brown hair and drew him onto his lap.

“I had a chat with Father Christmas last night,” he told Meri. “He said he had wanted to give you something very special, but he needed my help.”

“He did?” asked Meri, his black eyes met his Carson’s green ones. They were the eyes of an old soul. Carson had recognized them; from somewhere on the loom of life, a thread had tightened.

“Yes. He told me that he was going to give you a very special gift, but it was one you couldn’t see or touch.”

“Sounds like a lousy present,” said Meri with unusual passion.

“That’s what I told him,” laughed Carson. “But as usual Father Christmas knows more than we humble folk do. He only chuckled.”

“Did he have a big tummy? Did it jiggle?”

“That it did, and he said, ‘Carson, my boy,’ (he calls everyone boy, you see, because he’s older than time itself) ‘Carson, you said the very same thing when I gave the gift to you,’ and then I knew what he meant.”

“What did he mean?” asked Meri.

“He meant that your gift would be this,” Carson snapped his fingers, and a glowing yellow star appeared in his palm and spun in lazy circles in the air before winking out.

Meri stared at him. “How did you do that, Granddad?”

“Did you like it?”

“It was wonderful!”

“Would you like me to teach it to you? Would you like to learn to do that and lots more besides?”

Meri nodded emphatically. “I think it’s the most marvelous thing in the world!”

“That’s your gift.”

Merri looked thoughtful. “What about the books?”

“Those are my books, from my training as a wizard. Someday you’ll be able to read them and understand them. I’m giving them to you.”

Meriwether looked thoughtful as he considered all that lay before him.

“Well?” asked Carson, still a little worried.

“It’s a lovely present,” the boy said a little sadly.

“But?”

“I was hoping for a sled.”

“Oh, I forgot,” said Carson hurriedly. “Father Christmas also told me you were to have a sled next time I went to the shops.”

“Oh! That’s alright then!” said Meri perking up.

“Merry Christmas, Meriwether” said Carson warmly.

Meri threw his pudgy arms around Carson and gave him an enthusiastic, and very wet kiss. “Merry Christmas, Granddad!”